(Initially written December 2022; updated in October 2023 with newer graphics.)

More than two years ago, I wondered whether the Liberals were doomed to continue losing ground because of the West’s faster population growth, and I did a bit of preliminary graphing to see how they have fared in each province since the 1960s. Now I am tackling the question much more comprehensively.

And then party-by-party:

A few points stand out:

- Each Liberal coalition was qualitatively different. Laurier’s coalition was Quebec-dominant, but still needed important contributions from all other regions. Mackenzie King built a truly pan-Canadian coalition, the only time this has ever durably been done since Sir John A. Trudeau père was an Ontario-Québec alliance, while Chrétien and Trudeau fils have built Ontario-dominant coalitions.

- 2011 seemed like a momentous occasion, in that it was the first majority since the First World War that was built while essentially ignoring Québec. This seemed to presage the next century of Canadian politics, where Québec’s seat share will decline while the West’s will increase. But in history, Harper’s majority was not that exceptional: Diefenbaker and Mulroney did not need Québec for their majorities (Québec decided to tag along), while the Clark minority of 1979, similarly Quebéc-deficient, came only a few seats short of the majority line. The Western contribution to Conservative coalitions has gone up over time, reflecting its increased demographic weight, but not that significantly: the Diefenbaker wave in the West has never been matched since (even by the Reform Party, with its explicit appeal to Western identity), while recent Liberal gains in the Lower Mainland has brought this figure down. In sum, the West contributes about as much to the current Conservative party as it did to Stanfield and Clark’s PCs in the 1970s.

- There is a symmetry to the way that the West used to vote for third parties but have swung decisively into the Conservative column, and the way that Québec has moved from being a Liberal fortress to letting a third party speak on its behalf. The West’s strategy has the obvious drawback of leaving them marginalized during periods of Liberal government. Meanwhile, the Bloc Québécois retains a position of maximum leverage in case of minority government (and its existence makes minority government more likely). But it never gets to be in the government, either—it is the low-risk, low-reward strategy.

This exploration brings me to a point I have wanted to make about Canadian party systems more broadly.

We Are Currently in the Fourth Party System

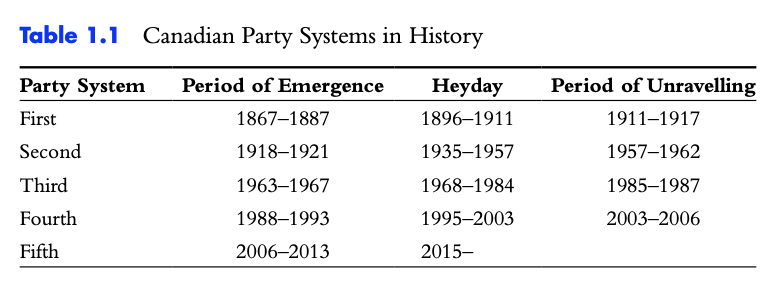

The prevailing narrative of the history of federal party politics suggests five “party systems”:

- The first system (1867-1911) was in the age of Macdonald and Laurier, where parties were loose coalitions of local representatives, drawn together by the prospect of patronage.

- The second system (1921-1957) was the Liberal-dominant period of Mackenzie King and Saint-Laurent, where Liberals were strong in most areas of the country, excepting Alberta. The party became a more cohesive entity, but Mackenzie King, the master of regional brokerage, created province-balanced ministries and delegated significantly to his various lieutenants in what has been called the “departmentalized” cabinet. This government undertook the construction of the welfare state to head off challenges from various farmer and labour parties.

- The third system (1963-1984) was the Liberal-dominant period of Pearson and Trudeau, where Liberals were strong in eastern Canada but the West had been swept into the Conservative camp by the Diefenbaker wave. This period of governance was marked by the centralization of power within the Prime Minister’s office (called the “institutionalized cabinet”). The government is best remembered for its symbolic nation-building exercises (official bilingualism and multiculturalism, patriation and the Charter) in the aftermath of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, to head off the threat of separatism.

- According to Steve Patten (2016), the Chrétien-Martin era is described as the “heyday” of the Fourth System, continuing the historical pattern where Liberal governments constitute equilibria while Conservative governments are interludes. The governments of Harper and Trudeau fils are the fifth system, marked by overwhelming centralization in the Prime Minister’s office and a stifling imperative of message discipline and permanent campaigning.

In earlier periods, it was sensible to mark the emergence of a new Liberal government as a sign of the political system settling into a new equilibrium state, but this is less justifiable now: in the 1935-1984 period they were in office for 42 out of 49 years; in the 38 years since, they have been in office for 20.

Party politics appears to have shifted from “punctuated equilibria” to continuous movement. From 1984 the Conservative camp contained both the West and Quebec; from 1993 it contained neither; from 2004 it reabsorbed the West. There was an anti-Trudeau backlash in 1984, an anti-Mulroney backlash by 1993, and an anti-sponsorship reaction by the mid-2000s.

I suggest that it is better to regard 2003 (the Conservative merger) as the beginning of the Fourth System, which still continues today. The same four parties have been the the protagonists, and the Liberals and Conservatives have both been able to rely on coalitions that are sizeable but generally fall short of a majority: the seven elections in this period have created five minority governments.

Here I don’t regard the Chrétien-Martin government as a party system in its own right: at the simplest level, the Ontario sweeps that made the Liberal majorities possible were solely the product of a divided Right and thus couldn’t possibly have represented a stable configuration. Instead, it should be seen as the second half of a grand transitional period. The failed referendum of 1995, and the ensuing freezing of constitutional debate, marked the end of a storyline that continued through Trudeau and Mulroney and the beginning of today’s constitutional status quo. The deficit-reduction push marked the end of Trudeau and Mulroney’s high-deficit era and the beginning of today’s paradigm, with its narrow bounds of debate regarding taxing and spending. Finally, this Great Transition saw a militant “grassroots” conservatism emerge to rival the PC party (with its strategy of mirroring the Liberals), then overtake and subsume it.

The main problem with this perspective is that it completely skips over the the 2011 Orange Wave in Quebec, one of the country’s most significant political earthquakes. But the conventional view has the same problem: 2011 is regarded not as a period of flux but a period where most of the characteristics of the “Fifth” Party System were already in full view.

While it feels off to describe everything between 1984 and 2003 as a “transition”, there is a historical analogue. The whole period between Laurier’s defeat in 1911 and the completion of Mackenzie King’s nationwide coalition in 1935 is considered to be outside any of the major party systems. Indeed, all of 1921-1935 is missing from Patten’s categorization altogether, and I think that choice is correct.

In short, the parts of the “Fourth System” that were new have continued onto the “Fifth System”: the “hollow party” possessing little more than leadership image, one-member one-vote leadership elections, the Reform Party challenge to the progressive cosmopolitan consensus, and “neoliberal” bounds of debate. Meanwhile, what makes the Fourth System distinctive (regionalization of elections) marks it as a transitional period instead.

Patten, Steve. 2016. “The Evolution of the Canadian Party System: From Brokerage to Marketing-Oriented Parties.” In Canadian Parties in Transition, Fourth Edition, 3-27. University of Toronto Press.

One thought on “How Canadian Party Coalitions Have Evolved (Or, Why We Are Still in the Fourth Party System)”